Shibori: A Short History and a Few Techniques…

Delve into the world of shaped-resist dyeing with Liz O'Brien. In this blog post, she explores the art of shibori, using everything from stitches to tongue depressors to create eye-catching patterns.

You may recall from my introductory post back in October that I’ve been interested in resist dyeing lately. Well, if you’ve stepped into the ADP studio at all in the last several weeks, you’ll likely have seen a scattered array of needles, thread, and cotton towels galore. During these last couple of months, I’ve been delving deep into the world of shaped resist dyeing techniques. In particular, I’ve been focusing on the art of shibori.

Shibori is an umbrella term that refers to the variety of ways cloth is embellished by shaping and securing it before it is dyed. The word shibori stems from the Japanese verb "shiboru" which loosely translates to “wring, squeeze or press.” Though shibori is used to designate a particular group of textiles, it also emphasizes the action performed on the cloth itself—the process of manipulating the cloth to create visual texture through controlled exposure to dye. If you’ve done any kind of tie-dyeing in your lifetime, you’ll likely be familiar with this concept of surface design.

Liz with an example of itajime-style shibori, created using tongue depressors

Liz with an example of itajime-style shibori, created using tongue depressors

Don’t be fooled, however. Shibori has a history much more complex than twisting a piece of cloth into a spiral and securing it with a few rubber bands. It has deep, ancestral roots dating back to 5th century China before being introduced to Japan around the 8th century. There are also some centuries-old examples of resist dyed textiles from Africa, Latin America, India, and other parts of Asia. Some of the Japanese shibori techniques we are familiar with today initially began as a means to make old, worn-out clothing look new. These patterns further evolved into folk art traditions that varied from region to region, from family to family, representing the infinite number of ways cloth could be tied, bound, stitched, folded, twisted, or compressed by an artisan's hands.

Liz created the spoons in this piece using the nui technique of stitching

In keeping true to its origins, my interest in shibori initially began with a desire to breathe new life into a set of old faded cotton kitchen towels I’d dyed a while back. Over the past couple of months, I’ve mainly been working with cotton fabric, though silk and hemp were also traditionally used. The primary dye was indigo and sometimes madder root, which I’ve been using as well as a few other dyes. There are several ways to create surface designs as mentioned previously, but the ones I’ve been spending quite a bit of time with lately include kanoko, itajime, and nui. Each style produces unique and striking results.

Kanoko is probably the technique we may be most familiar with as it is similar to regular tie-dye and is created by twisting small pinches of fabric and binding it with string (or rubber bands!) to block dye. Each knot is tied by hand and opened up one by one after the dyeing is completed.

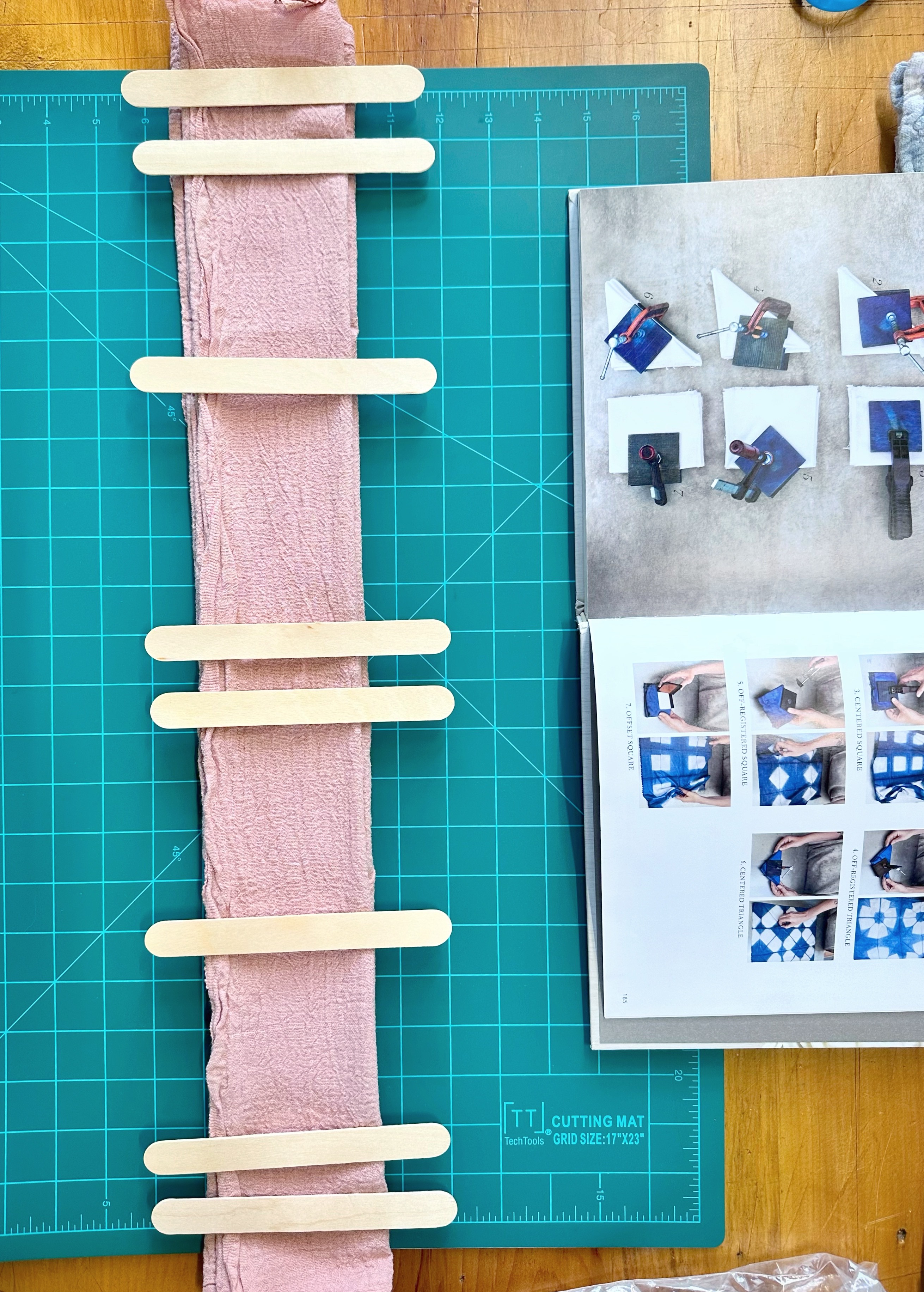

Itajime is traditionally created by placing two square blocks on either side of a tightly folded fabric, though using any shape can create unique patterns. The blocks are kept in place using clamps or string, and together they create bold patterns. In this photo, I used tongue depressors as my block resist of choice!

Nui is the technique I’ve been spending the most time with lately, stitching the outlines of countless spoons and dala horses. It is created using a simple running stitch on the cloth and then pulling it to gather it. Each thread is secured tightly in place before starting the dyeing process. Although nui allows greater control of the pattern being created, it is the most time-consuming of the techniques I’ve been exploring.

.jpeg)

In the many hours I’ve been stitching away recently, I’ve also been reflecting a lot on bridging the gap between tradition and modernity and how to honor this ancient craft while simultaneously finding new ways to creatively expound on it. I’m learning that the nature of shibori is to keep evolving. Whatever form this takes is still open to interpretation, but either way, I’m enjoying the journey along the way!